By Diana Foster, Ph.D., CEO, TOTAL Diversity Clinical Trial Management, Kim Kundert, RN/BSN, Sr. Vice President, Site Development Services, and Jerome Adams, M.D., Chairman of the Board, TOTAL Diversity Clinical Trial Management

Abstract

Background: Several studies have been completed to date using the DSAT (Diversity Site Assessment Tool), a validated and reliable instrument and the relationship to site practice in enrolling diverse patients. This study explores the variables per item presented within the DSAT as compared to site characteristics.

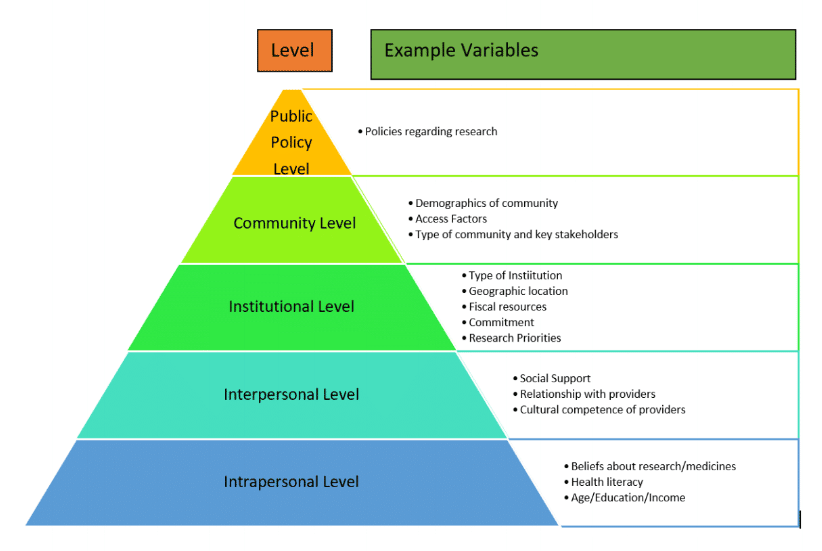

One of the yet unspecified advantages of a self-assessment tool such as the DSAT is that it can help create an agenda for systematic investigations into factors that are associated with clinical trials diversity recruitment best practices. To ensure that these investigations are carried out in a comprehensive and meaningful manner that contribute to the scientific discipline of solving issues pertaining to clinical trials diversity recruitment, this paper outlines a model that is adapted from the socio-ecological model published by Salihu et al.12

Methods: A cross-sectional, invitation-based survey research study design was utilized and circulated to a database of 920 clinical research sites. Over a period of three months, each participant answered questions pertaining to demographics of the site and they completed the Diversity Site Assessment Tool. The DSAT is composed of three domains, 1) Site Overview (10 items), 2) Site Recruitment and Outreach (9 items), and 3) Patient Focused Services (6 items). Each item in the DSAT is anchored to a 6-point scale (0 – No opportunity to observe, 1 – Hardly ever (< or = 5% of the time, 2 – Rarely (6-24% of the time), 3 – Sometimes (25-49% of the time), 4 – Often (50-74% of the time), 5 – Nearly always (75-94% of the time), and 6 – Always (95% or more of the time). All data from the completed responses was downloaded as an Excel sheet and checked for duplicate entries and incompletions. Descriptive and bivariate analysis were conducted to answer the specific research questions.

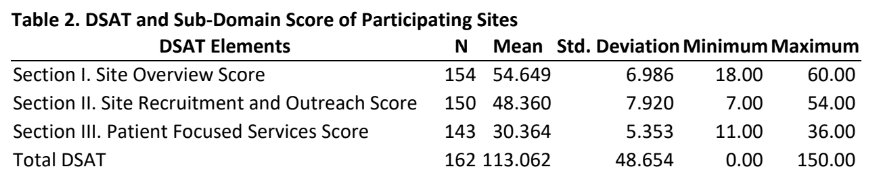

Results: The effective response rate was 18%. Majority of the participants were either from free standing (62%) or from physician practice/clinic (36%) sites. There was diverse participation in terms of research experience, membership in a network, US geographic region, interest in receiving training on diversity and inclusion, position, and research load. The mean scores for domain 1 (54.7+7.0), domain 2 (48.4+7.9), domain 3 (30.4+5.4), and total DSAT (113+48.7) indicated that participants nearly or always engaged in diversity recruitment best practices. Participants from the non-network sites (total DSAT 128.1+28.8) and low research load sites (total DSAT 130.4+29.5) reported significantly higher scores than network sites (total DSAT 110+48.6) and of high research load sites (total DSAT 116.8+40.2). None of the other variables were found to be significant.

A Determination of Variables That Impact Research Site Best Practices: An Analysis of Clinical Trial Site Characteristics as Compared to Related to Scores Using the SCRS Diversity Self-Assessment Tool (DSAT)

By Diana Foster, Ph.D., CEO, TOTAL Diversity Clinical Trial Management, Kim Kundert, RN/BSN, Sr. Vice President, Site Development Services, and Jerome Adams, M.D., Chairman of the Board, TOTAL Diversity Clinical Trial Management

Background

For the past several years in the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the leading regulator of pharmaceutical and biomedical products has promoted enrollment practices including broadening eligibility criteria and modifying trial design through a guidance issued in November of 2020 in hopes that would lead to clinical trial enrollment which was reflective of the population most likely to use the treatment. Despite these efforts, challenges to participation in clinical trials remain, and certain groups continue to be underrepresented in many clinical trials.

On April 13, 2022, the FDA released new draft guidelines with strong conviction that meaningful representation of racial and ethnic minorities in clinical trials for regulated medical products is fundamental to public health and achieving greater diversity in clinical trial participants will be a key focus throughout the FDA. The draft guidance recommends pharmaceutical sponsors develop and submit a racial and ethnic diversity plan early in their study planning stages.

Total Diversity Clinical Trial Management’s (TOTAL) Chief Executive Officer, Diana Foster PhD., has served as the strategy lead for the Society for Clinical Research Sites (SCRS) Diversity Awareness Program since 2016. SCRS is a global trade organization that serves as the voice of research sites. The Diversity Awareness Program was developed to generate an assessment of issues related to the recruitment of diverse patient populations in clinical trials, engage stakeholders in dialogue, and develop resources that would help strengthen site preparedness to improve the recruitment of racial and ethnically diverse participants. As CEO of TOTAL, these principles have been put into practice.

Part of the research conducted by this Diversity Awareness Program led to the development a site self-assessment tool titled Diversity Site Assessment Tool (DSAT). The DSAT is a tool that clinical trials sites can utilize for data driven strategic planning, communication, and resource allocation.7-11

A Model for Investigations of Variables Associated with Clinical Trials Diversity Recruitment Best Practices

The model specifies that behaviors either individual or organizational such as use of clinical trials diversity best practices can be influenced by numerous factors that act at different levels of influence. These levels of influence are intrapersonal, interpersonal, institutional, community and public policy.

The notable feature of these levels is that they are overlapping and can provide insight into an exhaustive list of factors that can influence behavior. For example, as outlined in Figure 1, policies related to research within a country can be a very influential factor on the focus towards clinical trials diversity recruitment best practices at the public policy level. Whereas at the community level, factors such as access to transportation and stakeholders who are knowledgeable about research become important influences.

At the institutional level, factors such as the priorities on research, funding for it, research productivity and commitment from leadership in terms of training and allocation of resources towards clinical trials diversity recruitment can be strong influencers.

At the interpersonal level, the level of social support, relationship with healthcare providers and the nature of communications can be important factors whereas at the intrapersonal level, factors such as beliefs about medicines, health literacy and socio-economic factors can be influencers for the extent to which diversity recruitment practices can become successful. It is important to note that the list of factors outlined in Figure 1 are examples of factors that can be studied but are not exhaustive over time.

In this paper, we showcase the use of this model by examining the relationship between a few key institutional factors and DSAT scores. The factors/variables investigated in this study include:

- Site Network Membership

- Region within United States

- Research Trial Load

- Site Diversity Training Interest

- Site Managerial Completion of the Diversity Site Assessment Tool

Specific research questions answered in this paper are:

- Is there a significant difference in DSAT scores between sites that are part of a membership network than sites that are not part of a membership network?

- Is there a significant difference in DSAT scores between sites that are from southern US than sites that are from other US regions?

- Is there a significant difference in DSAT scores between sites that have high research trial load than sites that have low research trial load?

- Is there a significant difference in DSAT scores between sites that indicate an interest in diversity training than sites that don’t indicate an interest in diversity training?

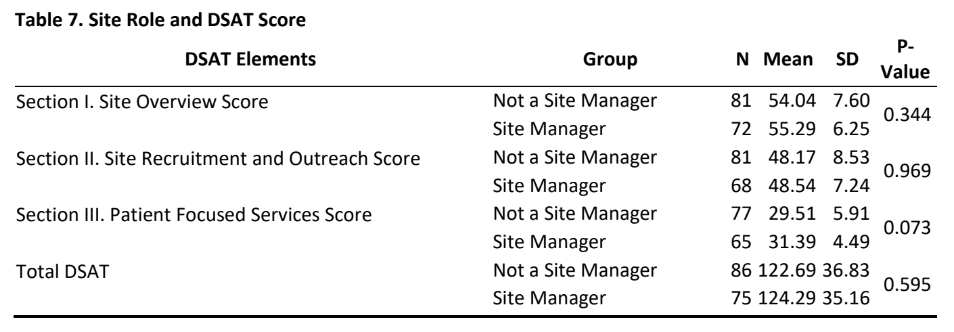

- Is there a significant difference in DSAT scores between sites whose managers completed the DSAT than sites who had non-site management completed the DSAT?

- Is there a difference in scores in any of the three sub-sections of the DSAT?

Methodology

Design: A cross-sectional design was used to administer a web-based survey (available on dsat.info) to collect data from the database of a leading contract research organization (CRO), TOTAL Diversity Clinical Trial Management.

Sample: A total of 920 representatives from clinical trial sites were invited to participate in the study via email with a link to the webpage on which participants answered questions pertaining to DSAT and background information about their site.

Data collection: The data was collected over a period of 90 days. The DSAT is composed of 25 items each of which are anchored to a 6-point scale (0-No opportunity to Observe, 1-“Hardly ever (<or =5% of the time)”, 2 – “Rarely (6-24% of the time), 3 – “Sometimes (25-49% of the time), 4 – “Often (50-74% of the time), 5 -“Nearly Always (75-94% of the time) and 6 – “Always (95% or more of the time) ). The 25 items are part of three sections: 1) Site Overview (10 items), 2) Site Recruitment and Outreach (9 items) and 3) Patient Focused Services (6 items). All data from the completed responses was downloaded as an excel file and checked for duplicate entries and incompletions. Descriptive and bivariate analysis were conducted to answer the specific research questions.

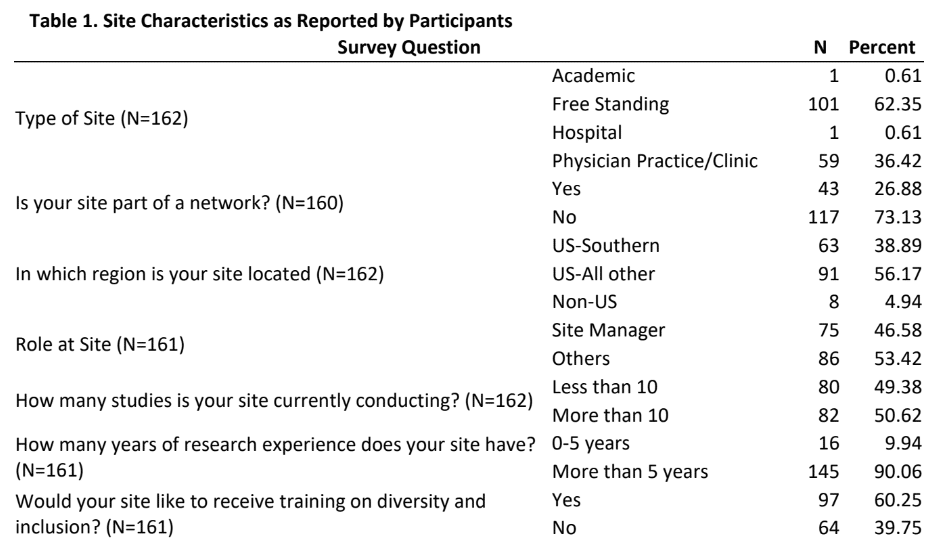

Results: Of the 920 individuals who were invited to complete the survey, a total of 162 provided usable responses for a response rate of 18%. Table 1 provides insights into the characteristics of the sites as reported by participants. The majority of the participants were either from free standing (62%) or from physician practice/clinic (36%) sites and had more than 5 years of research experience, approximately one-fourth were from a site that was part of a membership network, a little more than one-third were from the Southern US region. Approximately half of the participants were site managers and were conducting more than 10 studies. Table 2 provides mean scores and standard deviation for the three sections of the DSAT and the total DSAT scale.

- As can be seen from the mean scores, the average participant in this study reported scores that can be interpreted in the range of “nearly or always” engaging in practices that are included in a site overview, site recruitment and outreach and patient focused services as outlined in the DSAT.

- Unsurprisingly, the mean total DSAT for all participants were such that they can be interpreted as engaging in diversity recruitment best practices “nearly or always”.

Tables 3-7 provide analysis conducted to answer the research questions discussed earlier.

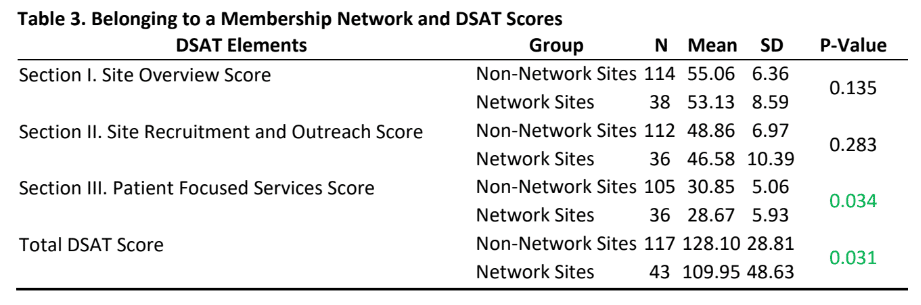

- Even though participants from the non-network sites reported slightly higher scores than network sites, there were no statistically significant differences in DSAT section I and II scores.

- Interestingly, there was a statistically difference for section III (patient focused services) and total DSAT scores (Table 3) indicating that non-membership network sites report engaging in more patient focused services that are considered as part of the best practices for diversity recruitment and overall best practices in diversity recruitment as measured by the DSAT.

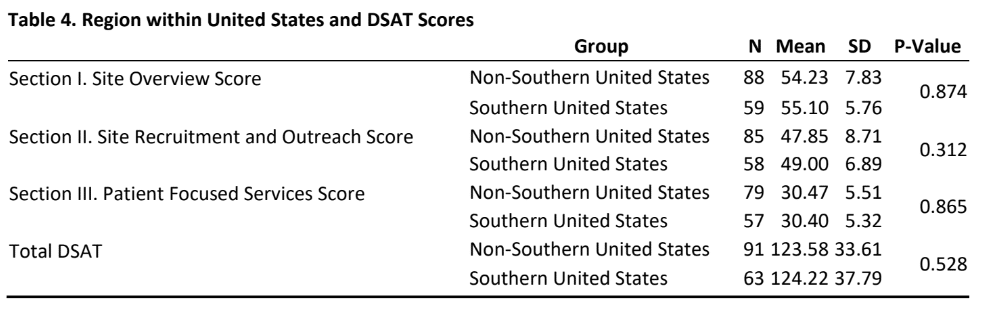

- As indicated in table 4, there was no significant difference in DSAT scores (section I, II, III and total DSAT) between sites that are from southern US than sites that are from other US regions. Table 5 provides insight into the relationship between research load and DSAT scores.

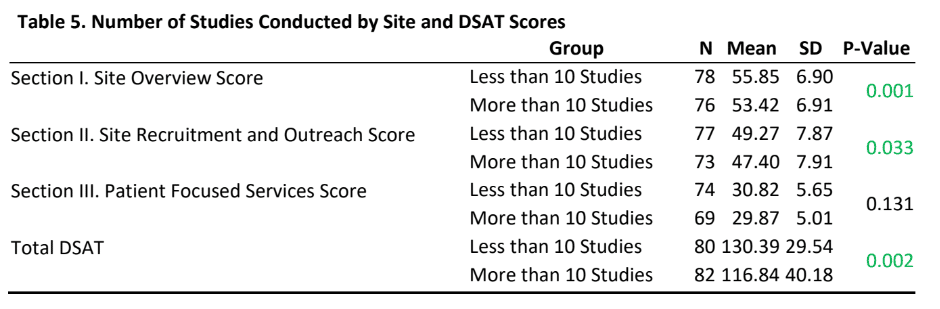

- Sites that currently have a research load of more than 10 studies reported statistically significantly lower scores on section I, II and total DSAT scores than sites that currently have a research load of less than 10 studies.

- There was no statistically significant difference in section III (patient focused services) DSAT scores between sites that have a research load of more than 10 studies as compared to research load of less than 10 studies.

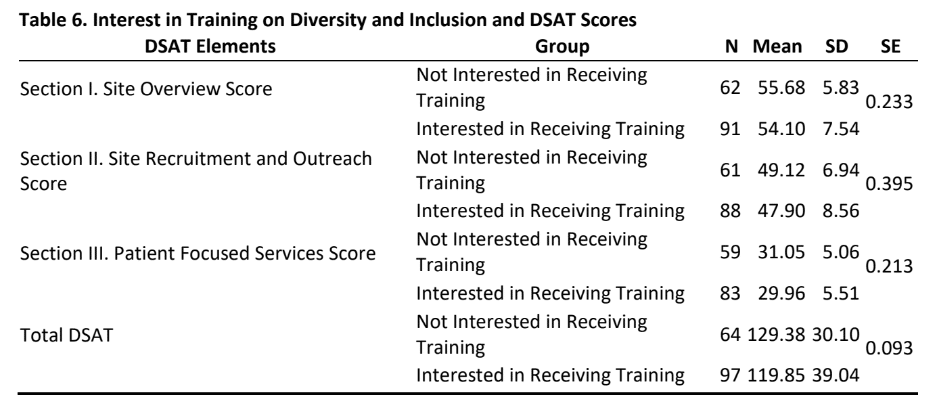

- As is evident from tables 6&7, there was no significant difference in DSAT scores (section I, II, III and total DSAT) between sites that had an interest in diversity training or not and for those sites whose managers or non-managers participated in this study.

Discussion: There is no doubt that stakeholders in the clinical trials industry are working individually and collectively towards improving diversity of enrolling patients in clinical trials. The assessment tool (Diversity Site Assessment Tool (DSAT)) that was developed to help stakeholders collect data on and use the information for strategic decision-making, communication, and integration of best practices. Yet, a framework for establishing a research agenda for investigations into factors or variables associated with clinical trials diversity recruitment best practices was much needed so that future systematic reviews13 can provide guidance for change.

To further that cause, the author has presented a model (Figure 1. A Model for Investigations of Variables Associated with Clinical Trials Diversity Recruitment Best Practices), which provides a template that researchers and stakeholders using the DSAT can utilize for identifying and conducting research on variables related to self-assessment scores on the DSAT.

Figure 1. A Model for Investigations of Variables Associated with Clinical Trials Diversity Recruitment Best Practices

- One of the notable findings from this study is that the mean scores for site overview, site recruitment and outreach and patient focused services domains as outlined in the DSAT are in the range of “nearly or always”. This is not only encouraging but also illustrative of the fact that key stakeholders and prominent groups in the clinical trials industry are expending tremendous efforts to promote diversity best practices during recruitment of clinical trials. These scores can also provide meaningful impetus for those sites and participants at those sites who may need that extra push for engaging in best practices for diversity recruitment.

- The finding that participants from non-network sites had higher scores than network sites on all three domains of the DSAT (and in the patient focused services domain) was interesting to note and raises questions about network sites such as: Are sites becoming part of a network because they know that they need to improve the integration of diversity best practices in their efforts and the network can help them in those efforts? It also raises questions about why non-network sites are not part of a membership network. Do these non-network sites feel that they have structured their patient focused services practices to aspirational levels and if yes, can these sites become “exemplar model” for other sites. A qualitative exploration of these questions may help the clinical trials industry sites develop significant learnings and partnerships.

- A significant finding of the study was that sites with higher research loads had lower scores on sections I, II and the total DSAT score than sites with lower research loads. While to some extent economic and organizational culture literature may help explain the fact that higher research load sites may indeed be operationally different than low research load sites, it becomes imperative to conduct further in-depth explorations of the impact of research loads on diversity best practices.

- Questions such as “Is it volume or is it standardization of processes or is it organizational culture and systems that is responsible for the comparatively lower scores?” need to be answered. The finding that there was no significant difference in DSAT scores (section I, II, III and total DSAT) between sites that are from southern US than sites that are from other US regions are encouraging and highlights that efforts towards diversity in clinical trials are being expended nationwide.

Limitations: As with any study that is based on a cross-sectional, invitation based and quantitative survey, the following limitations should be taken into consideration.

- First, majority of the participants in this study were mostly either from free standing (62%) or from physician practice/clinic (36%) sites. While this provides us with an excellent insight into self-assessment of diversity best practices in these sites, it becomes important to gather perspectives of participants from academic and hospital sites. Future research should try to utilize purposive sampling approach from these two clinical trials arena to help identify if diversity best practices are prevalent in these sectors.

- Second, the DSAT is a self-assessment tool and the survey required participants to self-report their self-assessment which may suffer from social desirability and positivity bias. Finally, the design of this study allows us only to make cross-sectional and quantitative observations that are based on provided responses. Further explorations and research using cohort and qualitative approaches are highly encouraged.

Conclusion: Overall, by providing a framework for examining factors influencing diversity best practices this study helps establish a future agenda for research on diversity best practices and based on the findings sets the clinical trials industry up with questions that it can use to further improve diversity best practices among clinical trial sites and partners.

Key Takeaways

- Provides a model that can be used for systematic investigations of variables affecting clinical trials diversity best practices

- High scores on section I, II, III and total DSAT scores indicate sites are engaging in best practices

- Participants from the non-network sites reported statistically significant higher scores than network sites for section III (patient focused services) and total DSAT scores

- Sites that currently have a research load of more than 10 studies reported statistically significantly lower scores on section I, II and total DSAT scores than sites that currently have a research load of less than 10 studies.

- No regional differences were found in DSAT domain and total scores

- Identifies that there is a need for participation from academic, hospital and institutional studies

References

- US Department of Health and Human Services Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. History and Development of Healthy People. Available at: History & Development of Healthy People | Healthy People 2020. Accessed April 29, 2022.

- US Department of Health and Human Services Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2030 Framework. Available at: https://health.gov/healthypeople/about/healthy-people-2030-framework. Accessed April 29, 2022.

- Foster D. Diversity and Inclusion in Clinical Trials. Available at: Diversity and Inclusion in Clinical Trials – Total Diversity Clinical Trial Management. Accessed: April 29, 2022.

- Guidance, Food and Drug Administration. Enhancing the Diversity of Clinical Trial Populations—Eligibility Criteria, Enrollment Practices, and Trial Designs. Accessed on April 29, 2022. Accessed from: https://www.fda.gov/media/127712/download

- US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. Scientific Advancement Plan. Available at: Scientific Advancement Plan (nih.gov). Accessed May 3, 2022.

- SCRS Launches Diversity Awareness Program. PRNewswire. 2017. Available at: SCRS Launches Diversity Awareness Program (prnewswire.com). Accessed: May 3, 2022.

- White Papers. The Society for Clinical Research Sites. Patient Diversity Awareness: Developing a Better Understanding of the Knowledge, Expertise, and Best Practices at Clinical Research Sites to Meet the Needs of an Increasingly Diverse United States Population. Available at: http://myscrs.org/learningcampus/white-papers/. Accessed: May 3, 2022.

- White Papers. The Society for Clinical Research Sites. Recruiting Diverse Patient Populations in Clinical Studies: Factors that Drive Site Success. Available at: http://myscrs.org/learningcampus/white-papers/. Accessed: May 3, 2022.

- Foster D. A Pilot Study to Examine the Validity and Reliability of a Site Assessment Checklist for Evaluation of Best Practices of Recruitment of Diverse Patient Populations for Clinical Trials. Insite: The Global Journal for Clinical Research Sites Summer 2020: Page 10-19. Available at: https://cloud.3dissue.com/180561/181052/211361/InSiteS ummer2020/index.html. Accessed: May 3, 2022.

- Foster D. The Diversity Site Assessment Tool (DSAT), Reliability and Validity of the Industry Gold Standard for Establishing Investigator Site Ranking. Integr J Med Sci [Internet]. 2020; 7:13. Available from: https://mbmj.org/index.php/ijms/article/view/266. Accessed: May 3, 2022.

- Foster D. Identifying Opportunities to Improve Diversity Recruitment. Available at: Identify Opportunities to Improve Diversity Recruitment – Total Diversity Clinical Trial Management. Accessed: May 3, 2022.

- Salihu HM, Wilson RE, King LM, Marty PJ, Whiteman VE. Socio-ecological Model as a Framework for Overcoming Barriers and Challenges in Randomized Control Trials in Minority and Underserved Communities. Int J MCH AIDS. 2015;3(1):85-95.

- Aromataris E, Pearson A. The systematic review: an overview. AJN The American Journal of Nursing. 2014 Mar 1;114(3):53-8.

About The Authors:

Diana L. Foster, Ph.D., is the CEO and chief diversity officer for TOTAL Diversity Clinical Trial Management, a diversity organization whose mission is to enhance diversity and inclusion in clinical research trials. Foster also serves as a consultant to the Society of Clinical Research Sites as Vice President of Strategy and Development, responsible for building relationships with industry that help amplify the voice of the clinical research sites.

Foster is a thought-leader and sought-after expert in diversity and clinical site best practices. She is the author of Diversity Site Assessment Tool and has authored numerous research papers on the topic. She has spoken extensively on the topic around the globe. She will be publishing a new text for the industry in 2022 titled, “need to insert title”.

Jerome Adams, M.D. is the Chairman of the Board for TOTAL Diversity Clinical Trial Management and the former U.S. Surgeon General. Former Vice Admiral Jerome Adams, MD, MPH joined Total Diversity Clinical Trial Management as Chairman of the Board in March 2022.

Dr. Adams also currently serves as Executive Director of Health Equity Initiatives at Purdue University. He formerly served as the 20th United States Surgeon General and as a member of the President’s COVID-19 task force, where he was at the forefront of America’s most pressing health challenges throughout the pandemic including working with companies to increase diversity in vaccine trials.

As the Chairman of the Board for TOTAL Diversity, Dr. Adams will share his in-depth knowledge of patient perspectives and industry views on diversity to create sustainable solutions and best practices to establish more diverse representation in clinical trials.

Kim Kundert, RN, BSN is the Senior Vice President of site development services for TOTAL Diversity Clinical Trial Management.

TOTAL Diversity is the only company offering a full range of diversity services to the pharmaceutical and biotech industry. In her role at TOTAL, Kundert is responsible for site support services as well as the Diversity Training and Education Institute (DTEACH), which provides instruction, guidance, and resources to research sites.

Kundert is a member of the Society for Clinical Research Sites (SCRS) Diversity Initiative Working group and has been involved with the Diversity Initiative since 2019. She also serves on the SCRS Diversity Site Assessment (DSAT) sub-committee. She is an expert at understanding and managing site/CRO relationships.